There’s nothing quite like a refreshing glass of water—except when it tastes like rust! If you’ve ever encountered water that has a metallic taste or noticed orange-red stains in your sink, you’ve likely encountered iron in your well water. Iron is an essential mineral for human health, but it’s not the kind you want to be sipping from your tap in high concentrations. This article explores how iron enters your water supply, the different forms of iron you might encounter, how to test for it, and how to deal with it.

How Does Iron Get Into Your Well Water?

Iron can enter your well water in two primary ways:

- Seepage: When rain or snowmelt travels through the soil, it can carry dissolved iron from the soil and rocks into your well water. In some areas, particularly in regions with iron-rich soil, this process can significantly increase iron concentrations in well water.

- Corrosion: Pipes and casings around your well—often made of iron or steel—can corrode when exposed to water and oxygen. As the metal deteriorates, it can cause the iron to oxidize which produces rust, which may flake off into your water supply.

What Are the Different Forms of Iron?

Iron in well water can appear in different chemical forms, each with distinct characteristics:

- Ferric Iron (Red-Water Iron): This is the form of iron that gives water its reddish or orange color. Ferric iron occurs when iron in water is exposed to oxygen and oxidizes, forming visible rust particles. If you notice reddish staining on your clothes, plumbing, or dishes, it’s likely ferric iron.

- Ferrous Iron (Clear-Water Iron): In contrast to ferric iron, ferrous iron is dissolved in water and can’t be seen until it’s exposed to air. Water containing ferrous iron may appear clear when it comes out of the tap but will turn reddish or brown after standing for a while. This form of iron often comes from deeper wells, where oxygen levels are lower.

To help remember the difference between the two, think of the ending of their names: Ferric ends in “ic”, and it’s the form you can see; Ferrous ends in “ous”, and it’s the one you can’t see unless it’s exposed to oxygen.

Does Iron Oxidize in Liquids?

Yes, iron can oxidize when exposed to liquids, particularly when it comes into contact with oxygen. This process is what turns clear water into rusty, reddish-brown water. When iron is dissolved in water (as in the case of ferrous iron), it’s stable, but once exposed to oxygen (either in the air or through contact with the soil or well casing), it oxidizes into ferric iron, forming rust. This is why your water might appear clear at first but discolor after standing or when exposed to air.

Signs of Iron in Water

There are several visible and sensory clues that iron may be present in your well water:

- Taste: Iron can give water a metallic taste that can be particularly noticeable when drinking it.

- Color: Water may take on a yellow, red, or brown hue, often staining dishes, laundry, and plumbing fixtures.

- Staining: Rust-colored stains may appear on sinks, bathtubs, toilets, and even clothing and fabrics, especially when washing.

- Clogs: Over time, iron buildup can clog pipes, wells, and appliances such as dishwashers, sprinklers, and water filters.

- Changes in Food and Drink: Iron can cause foods like potatoes to turn black and can affect the taste of coffee and tea, sometimes leaving a rainbow-like sheen on these beverages.

How to Test for Iron in Your Water

If you suspect iron contamination in your water, the next step is testing. While visible signs like staining and discoloration can be strong indicators, the exact level of iron can only be determined through testing.

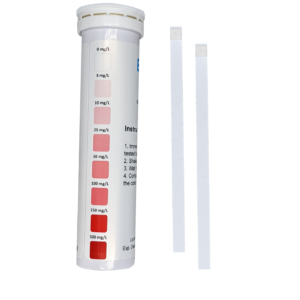

- Test Strips: Test strips are well suited for preliminary testing, when you would like to get an idea as to the approximate level of iron. They are generally lower cost but are generally less accurate than lab testing. We make an iron test strip that measures free soluble iron with a limit of detection of 0.15 mg/L.

- Laboratory Testing: The most reliable way to test for iron in your water is by sending a sample to a certified laboratory. This will help determine whether the iron level exceeds the threshold of 0.3 milligrams per liter (mg/L).

In addition to testing for iron, it’s helpful to test for water hardness, pH, and alkalinity.

Treatment for Iron in Well Water

The right treatment for iron in your water depends on the type of iron, its concentration, and the overall chemistry of your water. There are several methods for treating iron contamination:

- Ferrous (Clear-Water) Iron Treatment:

- Water Softeners: These are effective for removing low to moderate levels of ferrous iron. Some softeners can handle up to 10 mg/L of iron.

- Iron Filters: Systems such as manganese greensand filters can remove ferrous iron levels up to 10-15 mg/L.

- Ferric (Red-Water) Iron Treatment:

- Iron Filters: Filters designed to remove oxidized iron can handle ferric iron levels up to 10-15 mg/L.

- Aeration or Chemical Oxidation: Injecting air into the water or adding chlorine to oxidize ferric iron and then filtering it out is a more aggressive treatment method for higher concentrations.

Conclusion

Iron in your well water may not pose a significant health risk, but it can cause noticeable taste and aesthetic issues, including staining and clogs. Understanding the form of iron in your water and the best treatment options is essential for maintaining clean, clear water. Regular testing and appropriate treatment can help mitigate the effects of iron contamination, ensuring your water remains safe and pleasant to use. If you’re unsure about the presence of iron or how to treat it, consulting with a water treatment specialist or your local health department is a good place to start.

![DWQ12V25-main Total Iron Test Strips for Measuring Water, 0-10 ppm [Vial of 25 Strips]](https://bartovation.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/DWQ12V25-main-300x300.jpg)

![PWQ05V50-main Iron Test Strips, <span class="bldppm">0-100 ppm</span> [Vial of 50 Strips] for Measuring Free Soluble Iron (Fe2+ and Fe3+)](https://bartovation.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PWQ05V50-main-scaled-300x300.webp)